Panthers at Peralta

SUP draws inspiration from the birth of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense in October 1966 when Huey Newton and Bobby Seale met as students on 57th and Grove St. (now Martin Luther King Jr. Way) at Merritt College. Unlike today’s view of Peralta as a job training hub, the Panthers saw the campus as “not a typical institution for so-called higher learning. Grove Street College is what is called a community college: a place where, for a variety of reasons, people who don’t have an opportunity to attend larger colleges and universities go to seek knowledge and hope for a better life.” The Grove Street campus also represented a base for organizing the neighborhood and a place to demand self-determination for Black and all oppressed people via community control of the curriculum, operations and facilities of the College. While engaged in militant resistance to the District, rank-and-file Panther women built counter-institutions to reproduce their culture of struggle.

This piece is an effort to remember the lessons of their struggle.

-=-

Study and care

or

When Huey met Bobby

Central to the early Panther organizing at Merritt was the reinvention and radicalization of then-dominant liberal community organizing, Maoist anti-capitalist anti-imperialism and cultural nationalism, all rooted in the ghettos and traditions of Black struggle in the Oakland Flatlands. In these early years, Newton, Seale and other Merritt students from the Flatlands viewed mainstream white supremacist public education as a key site of struggle. Newton and Seale took classes at Merritt at a dynamic time when the Afro-American Association was a prominent fixture on Bay Area campuses. Robert O. Self writes that the Afro-American Association (which included Ron Dellums)

embraced a nationalism that fused black capitalism, Afro-centrism and Garveyite self-help…[the] Afro-American Association and the emerging black studies courses at Merritt College and the University of California at Berkeley began to circulate an eclectic collection of texts among black students in the East Bay flatlands: James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, Jomo Kenyatta’s Facing Mount Kenya, Kwane Nkrumah’s Neocolonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, E Franklin Frasier’s Black Bourgeoisie, classics by W.E.B. DuBois, the revolutionary writings of Che Guevara and Mao Zedong, and Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth.

In Seize the Time, Bobby Seale writes that while these texts were influential to his political development, Newton and others ultimately broke with the AAA for two reasons. Newton emphasized action including militant self-defense, for example by “throwing hands” on whites who tried to disrupt an AAA rally. Newton also felt that the AAA’s black capitalism was another form of domination of the Black working class: [Newton] “would explain many times that if a Black businessman is charging you the same prices or higher, even higher prices than exploiting white businessmen, then he himself ain’t nothing but an exploiter.”

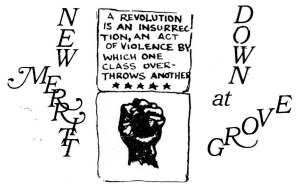

After Newton and Seale first met in 1966, they formed the Soul Students Advisory Council, a Merritt student group with cultural nationalist students and precursor to today’s Black Student Unions. Seale writes that the SSAC organized a large rally of 5-600 Black students at Merritt against the draft of young Black men to fight in Vietnam. But latent disagreements within the group came to the surface when Oakland Police tried to arrest Newton and Seale while Seale recited “Uncle Sammy Call Me Fulla Lucifer,” an anti-war poem with a political critique of education. Newton, Seale and their friends fought the OPD, but were eventually arrested and used SSAC funds to bail themselves out of jail, another source of feuding in the group. The division between Newton and Seale’s community-based anti-capitalist, militant self-defense politics and those of the cultural nationalists came to a head when, according to Seale, Newton proposed to SSAC that on May 19, Malcolm X’s birthday, they “bring these brothers off the block, openly armed, onto the campus, and bring the press down” to show “the racist white power structure that we intend to use the guns to protect our people.” The cultural nationalists disagreed (Seale says they were “scared”), and the Black Panther Party was born.

After Newton and Seale first met in 1966, they formed the Soul Students Advisory Council, a Merritt student group with cultural nationalist students and precursor to today’s Black Student Unions. Seale writes that the SSAC organized a large rally of 5-600 Black students at Merritt against the draft of young Black men to fight in Vietnam. But latent disagreements within the group came to the surface when Oakland Police tried to arrest Newton and Seale while Seale recited “Uncle Sammy Call Me Fulla Lucifer,” an anti-war poem with a political critique of education. Newton, Seale and their friends fought the OPD, but were eventually arrested and used SSAC funds to bail themselves out of jail, another source of feuding in the group. The division between Newton and Seale’s community-based anti-capitalist, militant self-defense politics and those of the cultural nationalists came to a head when, according to Seale, Newton proposed to SSAC that on May 19, Malcolm X’s birthday, they “bring these brothers off the block, openly armed, onto the campus, and bring the press down” to show “the racist white power structure that we intend to use the guns to protect our people.” The cultural nationalists disagreed (Seale says they were “scared”), and the Black Panther Party was born.

Black working class organizing in North Oakland and White New Left students at UC-Berkeley overlapped in dynamic ways; Self writes that “Merritt College and North Oakland emerged as the center of African American radicalism (soon, also, nationally).” The twofold political struggle over the content of classroom education and the production of knowledge outside of the schools via informal study groups was central to the lives of young militants in Oakland and Berkeley  in the mid-1960’s. A classic example of this rich political culture is Seale’s account of the awakening of Newton’s explicit political consciousness via Fanon:

in the mid-1960’s. A classic example of this rich political culture is Seale’s account of the awakening of Newton’s explicit political consciousness via Fanon:

One day I went over to his house and asked him if he had read Fanon. I’d read Wretched of the Earth six times. I knew Fanon was right…but how do you put ideas like his over? Huey was laying up in bed, thinking…plotting to make himself some money on the man. He said no, he hadn’t read Fanon. So I brought Fanon over one day. That brother got to reading Fanon, and man let me tell you, when Huey got ahold of Fanon, and read Fanon, Huey’d be thinking hard….We would sit down with Wretched of the Earth and talk, go over another section or chapter of Fanon, and Huey would explain it in depth. It was the first time I ever had anybody who could show a clear-cut perception of what was said in one sentence, a paragraph, or chapter and not have to read it again. He knew it already.

After the assassination of Malcolm X in April 1965, Newton – then an engineering student at Merritt – decided to start a formal Black history course. Newton bought a $35 UC-Berkeley library card to gain access to African and Black American history texts and started the Black History Fact Group, which “met three times a week at his house.” Seale describes how Newton’s in-class resistance produced the first Black Studies course:

Huey took an experimental Sociology course. I guess he’d been at Merritt a few years then. This experimental sociology course: he was running down to me how the course was for those in it to deal with some specific problem in society, and he swung the whole class to the need for Black History in the schools. Huey P. Newton was one of the key people in the first Black History course, along with many of the other people in the experimental sociology course.

But the story continues. When next semester Merritt had its first “Negro History” course in Fall 1965, it was taught by a White liberal “teaching American history…in the old traditional way they relate to black people in slavery.” Seale invited Newton to a class, where Huey took over and corrected the teacher’s errors on the history of the slave trade in Africa.

But the story continues. When next semester Merritt had its first “Negro History” course in Fall 1965, it was taught by a White liberal “teaching American history…in the old traditional way they relate to black people in slavery.” Seale invited Newton to a class, where Huey took over and corrected the teacher’s errors on the history of the slave trade in Africa.

Today in the student movement this dimension of struggle over the political content of education is largely secondary to budgetary demands. These are lessons to be relearned: the development of a positive set of demands, the intimacy of small groups reconciling political theory with their lived experiences, to sit in a friend’s bedroom and talk about Fanon.

-=-

Practicing community control

After World War II, working class Black families in West Oakland resisted the construction of new highways and above-ground BART lines that bulldozed their formerly tight-knit community and caused many families to lose their homes, forcing them to relocate to East Oakland. (Now largely deserted, Martin Luther King Jr. Way at 57th St. is split in half by brutalist concrete BART pillars.) War on Poverty programs of course failed to create wealth in the Black community, even as they increased the community’s interaction with and dependence on the Welfare State. In this context, the social reproduction and survival of the Black working class in the Flatlands became an evermore central concern of the liberal state as it attempted to respond to the Watts insurrection and the growth of confrontational, strategic direct action aimed at forcing employers to hire people of color. It was becoming clearer to Black youth in West Oakland that the white supremacist power structure was systematically eliminating their culture of struggle. This was a social context  where the very bodies of people of color–especially those of working-class women and their children, largely excluded from waged labor were–were maintained by the state as “bare life,” each day monitored and reliant upon an increasing number of social workers, bureaucrats, etc. Self-determination was a necessary counter to mid-1960’s interventionist federal and foundation-funded welfare programs that attempted to re-create resistance by channeling it in terms legible to state institutions.

where the very bodies of people of color–especially those of working-class women and their children, largely excluded from waged labor were–were maintained by the state as “bare life,” each day monitored and reliant upon an increasing number of social workers, bureaucrats, etc. Self-determination was a necessary counter to mid-1960’s interventionist federal and foundation-funded welfare programs that attempted to re-create resistance by channeling it in terms legible to state institutions.

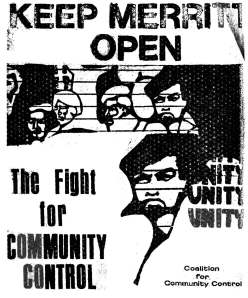

The Panthers and militant Black and Chicano students across the Peralta colleges fought against budget cuts to classes and aggressively took the offensive to use the Grove Street campus as a space for community programs. A central focus of the BPP was to recreate and maintain an independent community of resistance through its Community Survival Programs. Panthers – often led by women – created dozens of programs including the innovative Oakland Community School and a child development center where up to 80 kids would be raised collectively during the week and stay with their biological parents on the weekends. Crucially, rank-and-file Panther women created space for themselves within the organization to lead these programs and develop independent black feminist practice and theory. Wherever liberal state  institutions brought funding into the flatlands (schools, various welfare programs) the Panthers responded by building counter-institutions focused on care and reproduction meant to rebuild a collective autonomous political identity, beginning at birth.

institutions brought funding into the flatlands (schools, various welfare programs) the Panthers responded by building counter-institutions focused on care and reproduction meant to rebuild a collective autonomous political identity, beginning at birth.

The BPP’s first campaign at Merritt in 1967 was for the establishment of a full Black curriculum at Merritt. The Black Panther correctly predicted that “THIS TYPE OF CURRICULUM WILL BECOME THE STANDARD THING IN ALL BLACK COLLEGES IN RACIST DOG AMERICA.” In April 1969, the radical newspaper Guardian reported that Chicano students at Merritt won the naming of “a chicano member of the Socialist Workers Party head of a new Mexican-American studies department, free textbooks and meals for needy students and increased hiring of third-world people” when the students “barricade[d] the faculty into their meeting room and threaten[ed] the same to the trustees to win the demands.” This is one of the first examples of direct action at Peralta; it seems that historically, District intransigence makes confrontation necessary.

The BPP also contested the role of institutions that claimed to serve the community. “As the students and community work together to achieve community control of college boards, they can unite in demanding significant input and participation in the decision-making processes of the schools…and make the schools more relevant to the community,” writes Panther David Hilliard. Childcare in particular was central to the Panthers’ demands. At a Oct. 1972 talk by Huey Newton at Merritt College on Grove St., the Merritt College Reporter wrote that “The Panther leader said that day care centers must be established ‘to free the women in our society. Blacks are most oppressed in our society, and women are the most oppressed of the oppressed,’ he added.” At Laney, childcare, financial aid and free or affordable books,  transportation and food were central demands among students. “A militant fight against cutbacks in financial aid and community services will be waged so that members of the Laney College community can sustain their right to an educational institution which serves the needs of the community,” The Black Panther reported in Nov. 1975. That semester, the Laney Student Council proposed funding free legal services, creating a student/community council to investigate charges of discrimination and find funding for childcare and work-study. “In the area of childcare for students of Laney, the Program will insure the right for free and adequate childcare for both students and faculty members who require this service,” the Panther wrote.

transportation and food were central demands among students. “A militant fight against cutbacks in financial aid and community services will be waged so that members of the Laney College community can sustain their right to an educational institution which serves the needs of the community,” The Black Panther reported in Nov. 1975. That semester, the Laney Student Council proposed funding free legal services, creating a student/community council to investigate charges of discrimination and find funding for childcare and work-study. “In the area of childcare for students of Laney, the Program will insure the right for free and adequate childcare for both students and faculty members who require this service,” the Panther wrote.

Today, when the broader student movement is primarily struggling to revive schools that at best only partially serve our interests, we need to remember that these programs were born from struggle over the positive agenda developed independently by a previous generation of working-class people of color for their own survival.

-=-

The battle for Grove Street

In 1965, taxpayers in the Peralta Community College District approved a $47 million bond issue to finance four new campuses in North Oakland/Berkeley, East Oakland Hills (Merritt), downtown Oakland (Laney) and Alameda (COA). The Grove St. campus became a hub for militant Black organizing and a community resource center serving the Black working class in the neighborhood with a free library and free breakfasts. In response, the Peralta Board of Trustees systematically divested from the North Oakland campus through disproportionately large budget cuts to the campus and a lengthy delay in  planned building renovations. According to the Grove Street Grapevine, the Peralta Board “manipulated into insignificance” the individual Black Student Unions “as well as the needs of the communities [the Board] were supposed to represent. Having control of the money for the school programs and the financial aid they played the different schools against each other, making them scramble for pittance…The PCCD’s budget is one of their most closely guarded secrets.” The Peralta budget is still a mystery: for two years, Peralta simply didn’t pass a budget until April 2010. The current Peralta budget is still little more than a cryptic ledger without serious input from students and workers.

planned building renovations. According to the Grove Street Grapevine, the Peralta Board “manipulated into insignificance” the individual Black Student Unions “as well as the needs of the communities [the Board] were supposed to represent. Having control of the money for the school programs and the financial aid they played the different schools against each other, making them scramble for pittance…The PCCD’s budget is one of their most closely guarded secrets.” The Peralta budget is still a mystery: for two years, Peralta simply didn’t pass a budget until April 2010. The current Peralta budget is still little more than a cryptic ledger without serious input from students and workers.

The Panthers and their allies responded to the District’s divide/co-opt/conquer strategy in several ways. The Panthers and Black and Chicano student leaders at Peralta studied their enemies and used grassroots organizing and direct action to build power for their communities’ needs. Black students studied and researched in order to develop a political economy of how Peralta functioned as an institution and why the Board of Trustees made the decisions they did. Much of this research was published in The Grapevine, a multiracial radical newspaper based at Grove Street College and The Liberated Reporter, the Grove Street/Merritt BSU’s publication. Black student leaders needed a conscious, united base in order to win their demands. The Black Student Alliance, a union of the Black Student Unions at each of the four colleges, was formed in May 1972 to better coordinate their work and advance a common agenda. David Hilliard writes that the Black Student Alliance had a dual power role, duplicating many of the District’s programs and “institut[ing] a program for free books and supplies; a free transportation program; child care services; a financial aid program; a food program serving good, nutritious food at reasonable prices; and the initiation of relevant courses along with the demand for better instructors.”

Once the new Merritt campus in the Hills was opened, the Grove St. campus also remained open for several years at the same time. Rather than lament the slow death of their campus and call for its resurrection, the Merritt BSU turned crisis into an opportunity to build the education they wanted. Militant Black Merritt students built “cadres” including a pre-registration cadre to ensure incoming student sign up for classes at Grove St.; an equipment cadre to take inventory of materials and take action to keep them from moving to the Hills; and medical and day care cadres to organize a community free clinic and childcare for all students and community members who need it. They also planned to use the Grove St. campus as a space for a “People’s University” to continue Merritt’s Revolutionary Studies and ethnic studies programs.

A Feb. 1971 editorial in The Liberated Reporter calls on Merritt students to stop the removal of equipment and create student committees to replace teachers who took a job at the new campus in the Hills. The editorial feels fresh today as a rebuke to the broader student movement’s increasingly defensive and confused attempt to “save” education, and is worth quoting at length:

A Feb. 1971 editorial in The Liberated Reporter calls on Merritt students to stop the removal of equipment and create student committees to replace teachers who took a job at the new campus in the Hills. The editorial feels fresh today as a rebuke to the broader student movement’s increasingly defensive and confused attempt to “save” education, and is worth quoting at length:

In Spring, when our new People’s University will really begin, we will have a wonderful opportunity to rebuild or discard those elements of our education we dislike, and to reinforce or introduce those things which we accept as relevant and important. Let us all…use this temporary breakdown in ruling class control of Merritt.

We are all intelligent and creative people. We all have an idea of what we want to do with our minds and our bodies. We have a right to control our own jobs, our own educations, our own lives and our own destinies.

…if anyone here has ever been bored or frustrated by the administrative bureaucracy or by backward or reactionary or racist educational philosophy, let them take this opportunity to reorganize the structure of the classrooms themselves, whether they be student, faculty, staff worker, administrator or member of the community. We will turn the powers of the bureaucrats over to the people, through the Community Control Council which we will organize, and which will help us democratically govern our school, from now on.

This is the strategy of a militant, class-conscious, anti-racist student movement with a positive vision for their own survival.

Despite community protests that extended its life, the Grove Street campus fell into disrepair and closed due to a series of decisions made by the Peralta  Trustees and administration to systematically defund it. An Oct. 1972 issue of The Grapevine reported that “the old Merritt College…was in great danger of being lost to the residents of the North District area because of mismanagement of the $47 million allocated by the taxpayers and inflation, but student and community pressure forced the District to abandon immediate plans for the closing of the Grove Street site.” This ongoing pressure forced the Peralta District to lease facilities in Berkeley in 1973, which would become the Vista campus and later Berkeley City College.

Trustees and administration to systematically defund it. An Oct. 1972 issue of The Grapevine reported that “the old Merritt College…was in great danger of being lost to the residents of the North District area because of mismanagement of the $47 million allocated by the taxpayers and inflation, but student and community pressure forced the District to abandon immediate plans for the closing of the Grove Street site.” This ongoing pressure forced the Peralta District to lease facilities in Berkeley in 1973, which would become the Vista campus and later Berkeley City College.

The Panthers’ legacy of militant resistance to win self-determination continues at Peralta. In 2001, BSU activists and allies took over a Peralta Board meeting to demand the Trustees rename the Merritt College Student Lounge after Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale (they won). Several years later, Peralta contracted with a production company to create a documentary called Merritt College: Home of the Black Panthers which was meant to tell the story of the Panthers’ early days. In a July 17, 2007 request for additional funds for the project, the company’s then-executive director and current Peralta Marketing Director Jeff Heyman assures the Trustees that “the district would hold the copyright to the production that might produce a future revenue stream, the proceeds of which would return to the district…The film will show Peralta as a change agent for social change and can be used as a marketing tool.” So continues this cycle of struggle and recuperation.

-=-

Lessons to relearn

We are often confronted by a legacy of the Panthers as either a detoothed community service organization or all claws. But the BPP experience at Peralta shows the work of a multifaceted organic expression of a specific section of Oakland’s working class to overturn institutions that claim to serve them and remake them into bases for struggle. When the Panthers spoke of occupying a building, it wasn’t (only) to appeal for more funds from the state, but to keep the state away from self-organized community programs. This meant not simply a negation of racist, authoritarian educational institutions, but their redefinition and reuse. As the editorial of the first issue of The Grapevine wrote,

To the continuing students and student-workers, right-on to the work you have done and the work you have inspired your communities to do, right-on to your moves to secure your community institution, to moving for freedom from oppression, to moving to make this a real community college – in practice. We still have work to do, but we have reached a higher level of organizing and our work will be even more effective in the future. We will win our fight to keep our community college and control it.

This is a message to today’s student movement. Beyond “demand[ing] affordable, accessible and quality education” or “keep[ing] California’s original promise of higher education” lies the seizure and re-invention of these institutions around fundamental principles of self-determination, self-management and freedom from oppression.

Pingback: Bay Area Class Struggle History: Panthers at Peralta Colleges « Advance the Struggle

Pingback: Repost: Panthers at Peralta « Kloncke

Just wanted to say thanks for this excellent and inspiring history! Very helpful to me. Much gratitude.

Pingback: Shout Outs! |

Pingback: Defend and Transform Public Education | Advance the Struggle

This article is very well-written and powerful. We are from UC Berkeley and are currently working on a project on the Black Panther Party in Oakland. Kindly let us know if it would be possible to speak to the students who wrote this or how we could get in contact with the authors of this work.

Thank you.

Thank you for taking the time to post this, you clearly put a lot of research an thought

Searching for something else, I found this.

I am the Caucasian boy, dressed like a girl at the preschool.